In his recent interview with VatorNews, Healthmap Solutions (Healthmap) CEO Eric Reimer cited health equity as a major factor in the company’s rapid growth. Payer and provider organizations saw Healthmap’s comprehensive, value-based kidney care solution as a way to deliver quality care to previously underserved and underrepresented populations. Healthmap also helps organizations meet the accountability requirements coming out of the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS).

In this article, we’ll examine the challenges of kidney disease management for people of color, including:

- The incidence of kidney disease in minority populations

- Social barriers to care including access to care

- The federal initiative to close the gap in healthcare access

- How value-based kidney care can help

The incidence of kidney disease in minority populations

One in three Americans is at risk for kidney disease. However, as the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases notes:

- “African Americans are almost four times as likely as Whites to develop kidney failure. While African Americans make up about 13 percent of the population, they account for 35 percent of the people with kidney failure in the United States. Diabetes and high blood pressure are the leading causes of kidney failure among African Americans.”

- “A growing number of Hispanics are diagnosed with kidney disease each year. Since 2000, the number of Hispanics with kidney failure has increased by more than 70 percent. Compared to non-Hispanics, Hispanics are almost 1.3 times more likely to be diagnosed with kidney failure.”

- “American Indians also are disproportionately affected by kidney failure. Compared to Whites, American Indians are about 1.2 times more likely to be diagnosed with kidney failure.”

So, minority populations are more likely to develop chronic kidney disease (CKD) and progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Yet, according to the American Institute of Research:

- “Black or African American patients are less likely than patients of other racial groups to receive any kidney-related care before they reach ESRD.”

- “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are less likely than white patients to be referred for transplant evaluation, complete evaluation for transplantation, be placed on the waiting list, or receive a kidney transplant.”

Why is the incidence of CKD and ESRD higher in BIPOC populations? And what is preventing them from receiving an equitable level of renal care?

Social Determinants of Health and Access to Care

As the National Kidney Foundation points out, “Minority populations have much higher rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, all of which increase the risk for kidney disease.”

Their susceptibility to these chronic conditions is largely due to a poor diet (a lot of reliance on packaged meats, for example) and high levels of stress due to unfavorable socioeconomic circumstances (employment, neighborhood environment, family).

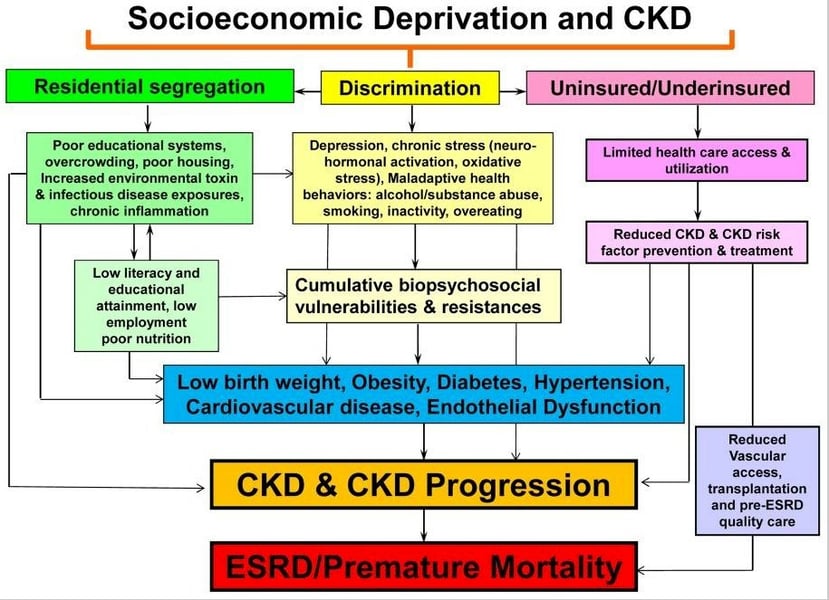

An article published on the National Kidney Foundation’s website Advances in Kidney Disease & Health included the graphic below:

According to the article:

“The figure shows that many of the determinants of CKD such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and endothelial dysfunction, as well as chronic inflammation, neurohormonal activation, and oxidative stress, may have their foundation in socioeconomic deprivation and its outcroppings or extensions. These include, but are not limited to, discrimination and segregation, substandard living conditions, limited quality health care to the uninsured or underinsured, limited health literacy, poor educational systems, and chronic stress that result in measurable and quantifiable pathologic factors that contribute to and enhance the development of CKD and eventually to ESRD and premature mortality.”

Until very recently, there has also been a race-based disparity in the algorithms used to measure kidney function. Because Black people tend to have higher creatinine levels in their blood than White populations, a modifier was put into the algorithms for estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR). It was thought that this adjustment would produce a more accurate eGFR, but it actually resulted in lower detection of CKD among Black populations, which led to reduced interventions and delayed nephrology referrals.

This was borne out by a study of the “Clinical Implications of Removing Race from Estimates of Kidney Function” published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The study found that:

“Removing race may increase the prevalence of CKD among Black adults from 14.9% to 18.4%. Concurrently, 29.1% of Black adults with existing CKD may be reclassified to more severe stages of disease, with significant clinical and pharmacologic implications. ... Similarly, the prevalence of CKD stage 4 or higher may change from 1.0% to 1.3%, affecting 0.29% of Black adults in which the race adjustment was removed from evaluations. When they were finally diagnosed, they had already progressed to late-stage CKD.”

This race modifier also contributed to another disparity, noted by the National Kidney Foundation:

“Although a kidney transplant is the optimal treatment for kidney failure, Black patients face barriers to access at every step of the process and on average wait a year longer than White patients to receive a kidney transplant. Black patients are less likely to receive a transplant evaluation, have less access to the waitlist, spend longer on the transplant waitlist, are less likely to survive on the waitlist, and have lower rates of graft survival post-transplant.”

A factor in the longer waitlist time is the dearth of Black kidney donors. While a same-race donor is not essential to transplant success, it has been shown to improve the odds. It appears that the same social determinants of health that put Black people on the kidney waitlist also make it difficult to find donors.

The Federal Initiative to Close the Gap

Efforts have been and are being made to root out the causes of health inequity and find solutions.

In 2000, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services launched an initiative called Healthy People 2010, one of its broad goals being to eliminate racial and ethnic healthcare disparities.

The movement began in earnest with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. According to a 2016 report published by the Journal of the American Society of Nephrologists:

“The ACA has been heralded as providing significant opportunity to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in access to health insurance and health care. Early assessment of changes to healthcare access following implementation of the ACA suggest it has already begun to equalize access to care by reducing disparities in insurance status. The prevalence of uninsured individuals decreased to a greater degree among both Black and Latino Americans compared with White Americans.”

Another decisive push came in 2021 when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced action to close health equity gaps in ESRD treatment. As the press release stated:

“Through the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS) annual rulemaking, CMS is making changes to the ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) and the ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) Model and updating ESRD PPS payment rates. The changes to the ETC Model policies aim to encourage dialysis facilities and health care providers to decrease disparities in rates of home dialysis and kidney transplants among ESRD patients with lower socioeconomic status, making the model one of the agency’s first CMS Innovation Center models to directly address health equity.”

And:

“Consistent with President Biden’s Executive Order 13985 on ‘Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities through the Federal Government,’ CMS is addressing health inequities and improving patient outcomes in the U.S. through improved data collection for better measurement and analysis of disparities across programs and policies.”

This was in addition to the alternative payment and accountable care models that have also been implemented to reduce healthcare costs and improve quality and outcomes.

Numerous institutions, professional associations, and nonprofit organizations have also spoken out on the issue of health equity and the need for change, especially in relation to the dramatic rise in CKD.

The Federal Initiative to Close the Gap

As Healthmap Solutions CEO Eric Reimer pointed out, Healthmap’s unique approach to value-based kidney care was quickly perceived as a pathway to equity in healthcare. The reasons?

Advanced data collection and analysis. Healthmap’s proprietary data analytics tools identify health plan members who have CKD (but may not have been diagnosed yet) and those who are most at risk. Identification leads to intervention when necessary.

Education and information. Patient education is one of the most important factors in health equity. Lower-income minority populations have less access to medical information and may not be able to fully understand what information is available. Healthmap ensures health information is shared in an equitable way for all, whether this means tailoring education to one’s preferred language or literacy level.

Ongoing patient and provider support. Healthmap’s team of Care Navigators, made up almost exclusively of RNs with kidney care experience, contact members and work directly with them to help them understand their condition, adhere to their treatment plan, make necessary diet and lifestyle changes to optimize their kidney health. Care Navigators also help members identify barriers to treatment, such as childcare and transportation, and connect them with resources in their local community.

Meanwhile, our multidisciplinary Quality Practice Advisors collaborate with and support providers across the full continuum of kidney care. They become a seamless extension of the provider’s practice, supplying current actionable information and clinically proven care recommendations.

An equitable, value-based kidney care solution must put the patient first and provide care for the whole individual, regardless of their socioeconomic situation. That is the value payers and providers have been finding in Healthmap’s NCQA-accredited Kidney Population Health Management program.

Don't forget to check out the VatorNews podcast with Healthmap Solutions CEO Eric Reimer here.